Roman Times

Name Bošana is most likely derived from the Roman period and comes from (Villa) Bassana, a Latin surname (nomen) of its owner, certain Bassanus.

This surname is most probably of Greek/Syrian origin, according to the imperial lineage of Severins that came from the Middle East. Namely, the Emperor Caracalla (Picture 1), son of Septimus Severus and one in the series of emperors of Syrian descent, was originally called Julius Bassanus and only after becoming Caesar he changed his name to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus out of respect for the family of Antonin. His maternal grandfather was Jacobus Bassanus, father of the famous Empress Julia Domna, wife of Septimius Severus.

From the lineage of Syrian emperors also came Emperor Elagabalus, originally Varius Bassanus (Picture 2), a very undignified Roman emperor, to put it mildly. His name Ela-Gabalus, which in Aramaic means God of the mountains, is sometimes confused with Helio-Gabalus, meaning the Sun God in Greek.

There was also a colony Bassiana in the 3rd century, located east of Sirmium, the capital of Pannonia inferior, which probably got its name from the Emperor Caracalla's surname Bassianus.

In addition to being a surname, bassus, as Bassus aqua or Bassus terrae, could also mean plain or the lowest point of something, which would in this case refer to the coast.

The site is laid out on both the sea and the mainland, as there are remains of a Roman port in the waters off the coast of Bošana that was fortified and partly explored. Unfortunately, the mainland part of the site in the immediate hinterland of the port is unexplored and unknown, so we have no knowledge about the position and appearance of the main building of the villa nor about the number of farm buildings and their purposes. (Picture 3)

Picture 1 - The Roman Emperor Caracalla (211-217)

Picture 2 - The Roman emperor Elgabal (217-222)

1 - Triclinium, 2 - Bakery 3 - Bathroom 4 - Kitchen, 5 - Stable, 6 - Yard, 7 - Press for grapes,

8- Yard for fermentation, 9 - Rooms for servants, 10 - Press for Olives, 11 - Barn, 12 - Place for grain threshing

Picture 3 - The appearance of the villa in the late 1st century

Picture 4 - Horreum - Roman warehouse

Picture 5 - Appearance of the Roman estate

.png)

Picture 6

Tile stamped PANS(IANA) late 1st century.

Picture 7

A ship that carried barrels

It can be expected that not all architecture from the Roman period was destroyed, as evidenced by the remains of Roman walls that became visible in the profile of the coast due to erosion. In the eroded profile of the coast directly above the port we can see a group of Roman walls that define an object, while the inside between these walls is filled with stone pillars that supported the floor of the object. This typical Roman design of the hollow floor is known as hypocaust.

In this case it was probably not a heated floor in the residential villa rustica but more likely the storage space Horreum, which was used for keeping goods close to the port. (Picture 4) This suggests that the villa's main building and other structures are yet to be found and explored.(Picture 5)

The site has been an immediate subject of interest of the first researchers and antiques enthusiasts in Dalmatia. First account of the Bošana site was given by Mr. Urlić Ivanović back in 1881, when he wrote that remains of a large well carved in stone as well as three roof-tiles and several lead pipes were found in the intertidal zone of the coast. The same author wrote that aqueduct has multiple taps on the section near Bošana, and about a swale that reveals a shaft of the water channel in the vicinity of, as he stated, the Church and the Cross. Also recorded was the finding of a Roman tomb covered with tegulae, containing a bone spoon, ceramic fragments and tegulae with stamps PANSIANA and SOLONAS on them. (picture 6)

A distinctive feature of the villa, or rather the seaport, is that it was connected with the nearby aqueduct Iadera - Biba which ensured a supply of fresh drinking water.The mentioned well on the coast and the Roman aqueduct Biba (Vrana) - Iadera (Zadar), which runs some 400 meters to the north, were apparently connected as was also pointed out by don Luka Jelić who claimed that the aqueduct had a branch that led to the Bošana site. This meant that the port Bošana was an important point during the Roman times for the passing ships to stop and resupply fresh drinking water on their journeys. Thanks to this feature, the port was also the starting point for the transport of water used to load the antique cistern on the island Frmić. (picture 7)

This small island in the middle of the Pašman channel, near the island Babac and the straits between the islands Muntan, Pašman and Babac, with very strong currents, had a boat dock, a tank of fresh water and a smaller object with unknown purpose, which are now submerged. Navigation through Pašman Channel was not easy at the time, due to strong sea currents that often changed direction several times a day so it was necessary to track these changes to ensure safe sailing. Roman cargo sailboats, filled with goods and having modest maneuvering capabilities, had to wait for favorable currents in order to sail through the passage between the islands of Pašman and Babac or Babac and land. Another point that should be taken into account is that the sea level in Roman times was 1.5 to 2 meters lower than it is today, making the Pašman channel slightly narrower but noticeably shallower and the sea currents stronger. For this reason, the channel had a number of smaller and bigger Roman ports and docks where the boats could moor while waiting for the direction of current to change.

This is also evidenced in the name of the islet Frmić in front of Bošana. (Frmić - from Ferma - to stop, while waiting for the channel currents to change direction and allow sailing towards Iadera and further north.) Along with the mentioned system of ports, there had to be a communication system so that the information about the strength and direction of currents that varied daily could be exchanged.

The recent researches in Bošana were mostly focused on the underwater part of the site and the area where the antique port and dock were. Prof. B. Ilakovac covered the underwater part in the 1970s, when his reconnaissance showed the existence of two docks. Both docks are "L" shaped, with the western bank being built out of large broken blocks and smaller quarry stone, and the eastern pier being a wide mound of carved tone. Researches of prof. Z. Brusić are also of considerable importance. All underwater sites that we know of today were identified and described in his reconnaissance and offshore exploration of the Pašman channel, which widened our knowledge of the Bošana locality.

The latest underwater research, conducted by M. Ilkić and M. Pešić in 2009, gave a broader view of the archaeological material from the seabed in front of the villa. The remains of the Roman port installations were further confirmed by this campaign, as was the straight part of the waterfront with edges built from coarse cobble stone, and the port consisting of two breakwaters whose stone ruins stretched perpendicular to where the coast is today. The first breakwater, that protected the harbor from southern winds, was L-shaped in accordance with B. Ilakovac's findings in his first reconnaissance. The longer arm of the L shape is nearly 80 m long and the shorter stretches about 40 meters to the west. Existence of a smaller breakwater to the west is also confirmed, with the purpose to protect the harbour against the western and northwestern winds.

Istraživanje sondama provedeno u moru otkrilo je bogat kulturni sloj u kojem su osim obilnog keramičkog materijala pronađeni značajni nalazi: drveni koloturnik koji je bio sastavni dio brodske opreme rimskih brodova, mala brončana pređica kao dio osobne nošnje, ostaci koštane igle s kuglastom glavom za kosu te stakleni žetoni za zabavu. Spominje se nalaz velikog broja maslinovih koštica koje svjedoče o lokalnoj maslinarskoj proizvodnji.

Underwater research with probes revealed a rich cultural layer. In addition to abundance of ceramic material, other significant findings included a wooden pulley that was a part of equipment of Roman ships, a small bronze buckle that was part of personal attire, remains of a bone hairpin ornament with a ball head, and glass tokens for games. Another interesting finding is a large number of olive pits which testify to the local olive growing production. The sea floor around Bošana today is still covered with a large number of broken pottery vessels, amphorae of various sizes, along with smaller dishes, bowls and tegulae and imbrexes (large Roman tiles) which may have been parts of the coastal architecture or the shipped cargo. There is also a number of ballast stones that the ships discarded when needed in order to improve sailing.

If we compare the visible amount of pottery and shipping materials that are found in the sea around the Bošana port to the similar sunken port facilities from the era of Roman domination that we have in the vicinity, such as Kumenat, tank with a pier on Frmić, huge dock Polačine on Pašman in Kraj, the port in Neviđane, as well as Galešnjak and Garmenjak, we come to the conclusion that this was a very important port that served well above just the needs of the Roman villa rustica farm to ship their products. An exception could be the Roman port in Pakoštane as it is larger in area and probably has more findings than Bošana.

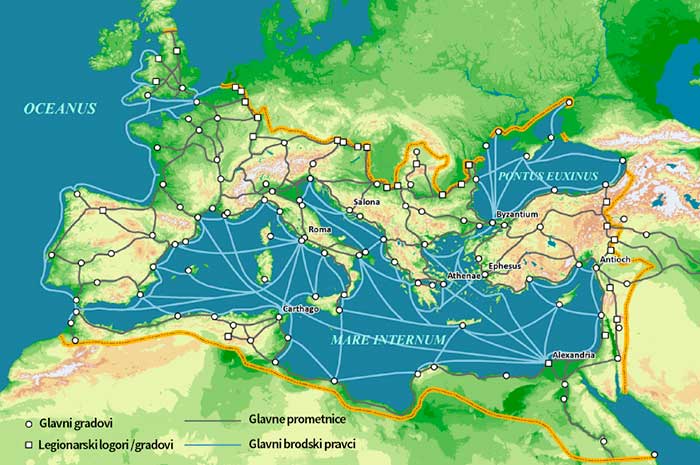

The found remains of representative and common kitchen ceramic goods, that had arrived from distant workshop centers scattered from southern Italy, eastern Mediterranean and Ionian coast, attest to the importance and connections that this port had with the entire Mediterranean during the Roman era. The fact that, all along the Adriatic coast, we found identical and very similar types of ceramic cookware originating from the east of the Mediterranean also points to the importance of the waterway to the north along the east coast of the Adriatic Sea in which the Pašman channel had an important role. High number of findings of pottery that originated from activities in the sea port in antiquity suggests the importance of some ports, namely that they also served to local communities as a point of entry to the sea. By analyzing primarily ceramic material, it was dated that the Bošana port was active in the period from the 1st to the 4th century, with increased commercial activities during the 2nd and 3rd century. (picture 8)

Picture 8 - Map of the Mediterranean in 125

As we have already proposed, due to its good maritime transport connections, the port Bošana was suitable as a port for the towns and communities in the immediate hinterland. It is important that we mention Blandona here, a Liburnian town which was located in the hinterland of Bošana, somewhere in the area between the Trojan town in the hamlet Stabanj and the near-by locality Gradina on the same plateau above the Vrana field. There is a path today that leads straight from Sokoluša through the Vrana field, and if we were to extend it with an imaginary line towards Jankolovica and the sea it would end in the Bošana site as the closest point where the ships docked in Roman times.

Gentle coast and bays suitable for the production of salt were among the biggest advantages for most rustic villas in the Pašman channel. Many toponyms refer to salt production: Slanica, Soline, and most probably the bay Jaz in the north-east part of the Biograd peninsula, today's site of marina, which most likely also featured salt pans as it has a favourable configuration with slight decline and large surface area, especially in times when the sea level is lower. Salt has always been a necessary and highly demanded product for the population in the Dalmatian hinterland and beyond, especially for the livestock farming community which would not be able to survive without salt.

Two stone findings from Bošana

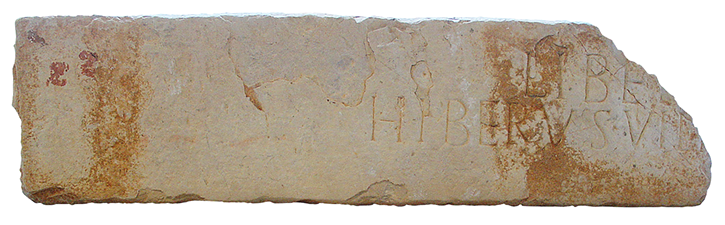

During the underwater excavations, a Roman inscription was found dedicated to the god Libero, the old Italic deity of fertility and patron of viticulture, which is linked with the Greek god Dionysus and his Roman version Bacchus due to having similar characteristics.

A writing on the well processed stone beam reads

LIBER O PATRI (?) SAC (rum) - To Liber, the holy father

HIBERUS VILICUS FEC(it) - Palafox (name) vilicus (the supervisor of slaves) made (picture 9)

Picture 9 - The inscription from Bošana with a dedication to god Liber

Picture 10

Depiction of god Liber

Picture 12

Depiction of goddess Cybele (Magna Mater) from Ostia

On the day of his festival in Rome (Liberalia, March 17), young men aged 15 were given masculine toga (toga virilis) and enrolled in the list of citizens. Him and his wife Libera, patron of agriculture, were Bošanian popular couple throughout the empire.

Emperor Gallienus 260-268 named Libero one of the sponsors of his reign and in one of the issues of his money the front reads Libero P(atri) Cons(ervatori) Avg(usti). To Libero, father saint protector. During the Roman emperors after Gaijen, god Libero is right behind Jupiter in popularity, making him a very significant and represented deity throughout the empire. (picture 10)

This inscription to Liber could have been intended for some customer in the hinterland, but also a part of the architecture of the villa rustica, that being a logical choice of protector. The goal of research on the land part of Bošana would be to find the remains of the sanctuary of God Liber. As a protector of wine-growers and vineyards, Liber would suggest that the main agricultural activity of the villa rustica Bošana was cultivation of grapes and wine-making. However, the multitude of olive pits found by probes inside the port and the fact that the fields are near the sea, exposed to salt and winds, give preference to the deduction that olive growing was a more suitable activity. In that case, we should be able to find some remains of facilities used for olive oil processing.

Apparently, a private collector in Biograd has in their collection a lower part of a stone statue that was found in a landslide profile on the Bošana coast. Although the found part is fairly damaged, it clearly shows a foot to the height of the ankle with a Roman sandal, and above we see an outline of the rich draperies of a toga. This could have been just another part of a statue with unknown attribution were it not for the display of a part of an animal leg from feline family next at its foot. Such display of deities with a cat that twists around their legs are commonly found in depictions of Libero-Bakh in several reliefs from the Roman Empire. It is consistent with these findings and the found inscription dedicated to Libero that we assume the attribution of the fragment of the statue to the same God which certainly had a dedicated place in the villa. (picture 11)

Picture 11 - Fragment of a statue from Bošana, representation of god Liber or Cybele

Besides Libero this fragment of the statue could have belonged to Cybele, Magna Mater (Great Mother), the Roman goddess of fertility. This deity originates from the area of Asia Minor and Middle East back in pre-Greek times. It was known as goddess Rhea in Greece and later became Cybele in Rome. The goddess was usually presented in sitting posture with the knees emphasized by more rigid folds of toga with the feet in sandals always visible under. It is characteristic that a lion, a leopard or some other large carnivore of the feline family would be displayed to the left or right side of the leg. The fragment of the statue from Bošana fits in its appearance to the statue of Cybele, Magna Mater from Ostia, which has a withdrawn right leg with a lion at its foot. (picture 12)