Middle Ages, Renaissance

Picture 1

Benedictine monastery of St. John

Picture 2

Benedictine convent of St. Thomas

.jpg)

Picture 3

The Church of St. Rocco - Rogovo, mentioned as royal estate with a village and palace from the 11th century

Picture 4

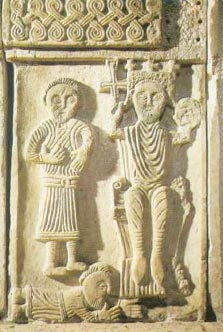

Pluteus, part of the baptistery from the Split Cathedral, the 11th century considered by some to be a representation of King Peter Kresimir IV.

Picture 5

Biograd cathedral in the 11th century, the Bishop residence.

The site where the Roman villa rustica and later the church of St. Andrew used to be is located on the belt of fertile land from the sea to the end of the Kosa locality, which was especially valued in the Middle Ages as the backbone of economic system and a synonym for wealth. Biograd's surroundings and hinterland is relatively rich with belts of fertile land, a very important feature in Dalmatia where good quality land is scarce and often insufficient for agriculture thus making the Bošana site particularly valuable. The fact that the the area had already been cultivated in earlier times meant that it could again be brought to purpose with less effort.

It was customary in the Middle Ages that the kings would donate estates when monasteries or churches were built as a sign of their devotion and concern for their souls, and a symbol of loyalty to the church. Following the same principle, Bošana ended in the charter of the Croatian King Petar Krešimir IV from 1060.

With this charter, King Petar Krešimir IV initiated the founding of the Benedictine monastery of St. John (picture 1) and convent of St. Thomas (picture 2) in Biograd, and donated royal estates to them, describing the locations and their borders. We should point out here that the most important gifted royal estate was Rogovo with a palace and a village towards the slope facing Nadin above Sv. Filip i Jakov near Biograd. (picture 3) The royal land in Basana (Bošana), located along the coast where the old church once stood, is also on the list of the mentioned estates.

This information about the existence of an old religious building in the area Bošana was very important for the people in 1060. That church could have been a renovated Roman building from the area of the former villa rustica or an early Christian sacred building from 4th or 5th century that somehow survived until the 11th century. Most likely scenario is that the church on the coast in front of Bošana where the ships anchored was built during the Justinian's Reconquista in mid-6th century, which is connected with the selection St. Andrew as the titular of the church as he was an Apostle popular in the east as well as the bishop of Constantinople.

The fact that the church survived for centuries after its establishment in the 6th century leads to the conclusion that it had to be restored during this period. The care and restoration had to be under the jurisdiction of the Byzantine Empire at least for as long as there was a waterway secured by the empire along the eastern Adriatic coast where Biograd and the port Bošana were important. We have no information that would shed light on the events surrounding Bošana during 7th and 8th century. It is certain that as of 9th century, due to Frankish conquest and the emergence of Croatian principality and kingdom, the Byzantine Empire lost some of its positions on the shore while still holding some islands and urban centers on the Adriatic under control. The Biograd peninsula and its surroundings probably came early under Croatian rule. In his work "De Administrando Imperio" from 10th century, the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (905-959) mentioned 9 populated cities in, as he called it, "baptized Croatia", featuring for the first time the "kastron Belgradon", the core of future Biograd.

Benedictines

In the period after the Great Schism and demarcation between Eastern and Western churches in 1054, this part of the Adriatic fell "de facto and de jure" under the jurisdiction of the Roman Church, which created the need for the church to strenghten its new position.

One of the first religious orders to work in that regard were the Benedictines who were universaly present in Dalmatia, Croatia, Boka Kotorska, and Sirmium from the 9th to the 14th century, founding over 100 monasteries in the effort to spread influence of the Western Church. Although the Benedictines are present in Croatia since 821, when entire of Croatia came under Frankish rule, their rejuvenation through strengthened Roman Church influence in the second half of the 11th century led to a new wave of construction of Benedictine monasteries.

Activity of the Croatian king Petar Kresimir IV (picture 7) should also be viewed with this in mind as he meets the requirements of the Pope and helps spreading this Order throughout the Croatian kingdom. It can be argued that he gave them a particularly great honor by placing two monasteries in his regal city where they were donated the finest royal estates. In order to adapt to the surrounding community in which they are active and where the Slavic language was dominant, the Benedictines have started remarkable works in the scriptoria of their monasteries to translate religious books from Latin to Church Slavonic (Old Church Slavonic). First text that was necessary to translate to Old Slavonic were the Regulations of St. Benedict. We have a known transcript of these regulations from the 14th century that was created in the monastery of St. Cosmas and Damian (picture 4) on Ćokovac which was made on the basis of the template from 12th century or earlier.

This leads to the assumption that the first translation of these regulations to Old Slavonic was made in the scriptorium of the monastery of St. John the Evangelist in Biograd, and by analyzing the language of the old Croatian edit it had a mixture of Old Slavonic and local expressions. (picture 5) The letter used by the Benedictines was Latin alphabet, but since the Glagolitic was equally used in Slavic countries, they advocated the Slavic language to be used in Church teachings and services. Glagolitic alphabet was one of the alphabets developed for Old Slavic language which was created in the 9th century by Constantine Cyril, a Byzantine monk from Thessaloniki. From the 12th century Glagolitic alphabet was no longer in use in the Slavic countries as it was replaced first by the Cyrillic and from the 16th century the Latin. A special feature in Croatia was the continuing use and development of the Glagolitic alphabet, transforming it to angular Glagolitic script during the 13th century.

The fact is that the Church in Croatia, just like elsewhere, was one of the main sources of literacy in both religious and everyday life, and the most deserving for preserving Glagolitic alphabet through many centuries all the way to present. (picture 6)

The fate of the church after it was given to the monastery of St. John the Evangelist is unknown but it seems it continued to have some function and was renovated. One of the major question to solve the issue of dating ot the church is whether the stone church furniture, dated to the end of the 5th and early 6th century and used for the Biograd Cathedral built in the 11th century (picture 8), was transferred from this church or did it come only from the early Christian church of St. Mary from Glavica in Biograd.

The church of St. Andrew existed during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance during prosperity Rogovo abbey, and later thanks to the care of Benedictines from Ćokovac. The church had to be rebuilt several times because of the frequent conflicts in the region, mainly due to the ravaging first by the Venetians and later because of the repeated Turkish invasions.

It is undisputed that the Bošana site was particularly important for the abbey of St. John the Evangelist as they built a port for the purposes of the estate Rogovo (molum Rogue). Several positions along the coast in the area Bošana are possible locations of the stone pier. This port was created to facilitate maritime communication with the wider region and especially for connection with the Benedictine monastery of St. Cosmas and Damian on the hill Ćokovac, Pašman. The Benedictines chose and were given the monastery on the Ćokovac hill after their return from Šibenik where they had taken refuge after the Venetian destruction of Biograd in 1125 when their monastery of St. John was destroyed. The Benedictines remained on Ćokovac because of the uncertain times that have ruled for the next 400 years. The wish to return and rebuild the monastery in Biograd was hindered as the order gradually lost its size and importance, while Biograd and its hinterland was ravaged during the Ottoman times.

It is well-known that the definitive end of this church came as a consequence of the Turkish invasion of Biograd during 1646 when the Turkish army cannons fired towards Biograd and Pašman channel from this position in Bošana. After the destruction of the church, it has never been renewed and was forgotten.

Picture 6

St. Cosmas and Damian

Picture 7

Angular Glagolitic, old Croatian script used by the Benedictines

Picture 8

Benedictine monastery of St. Cosmas and Damian on the hill Ćokovac, Pašman